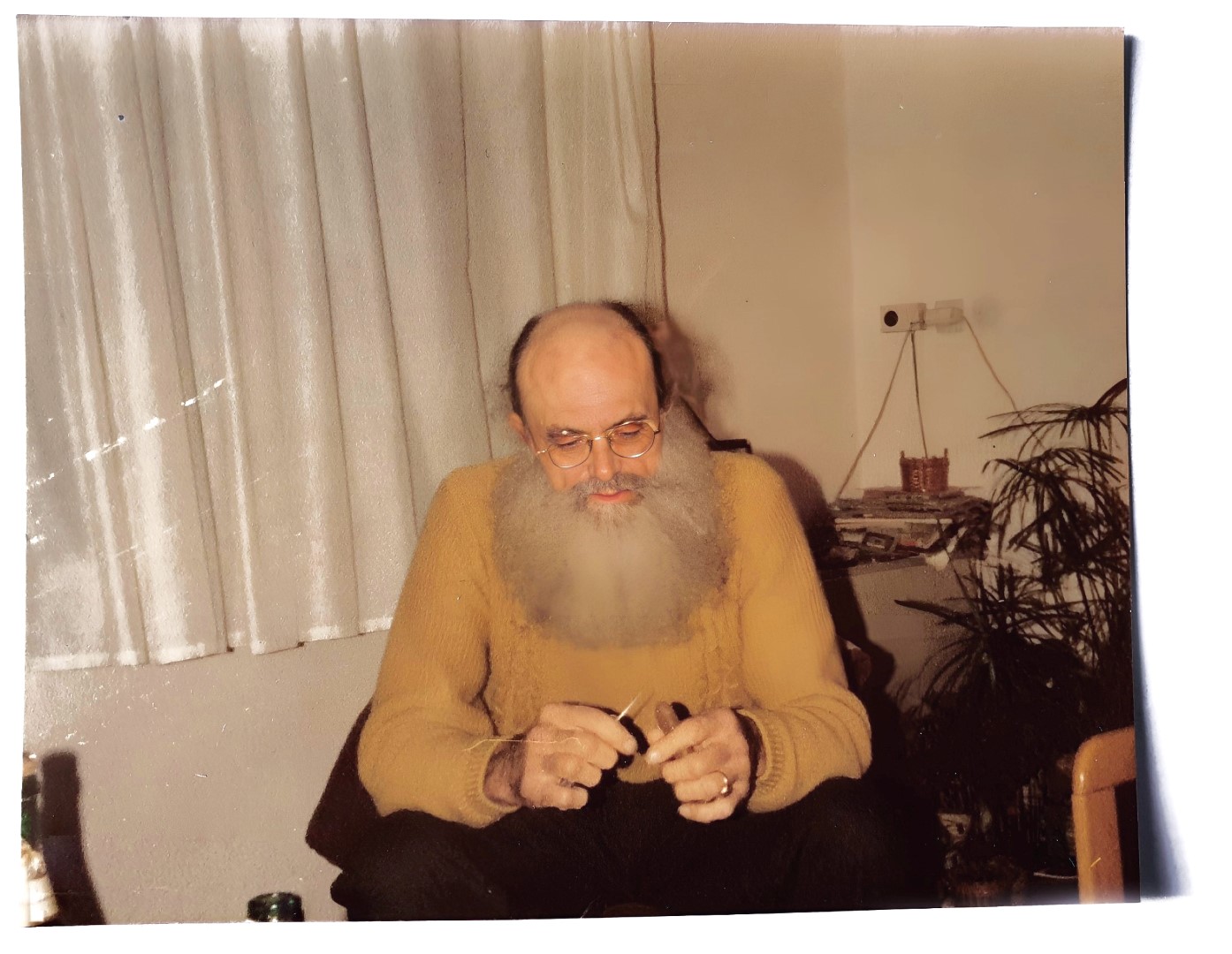

Grady Louis McMurtry (1918–1985) |

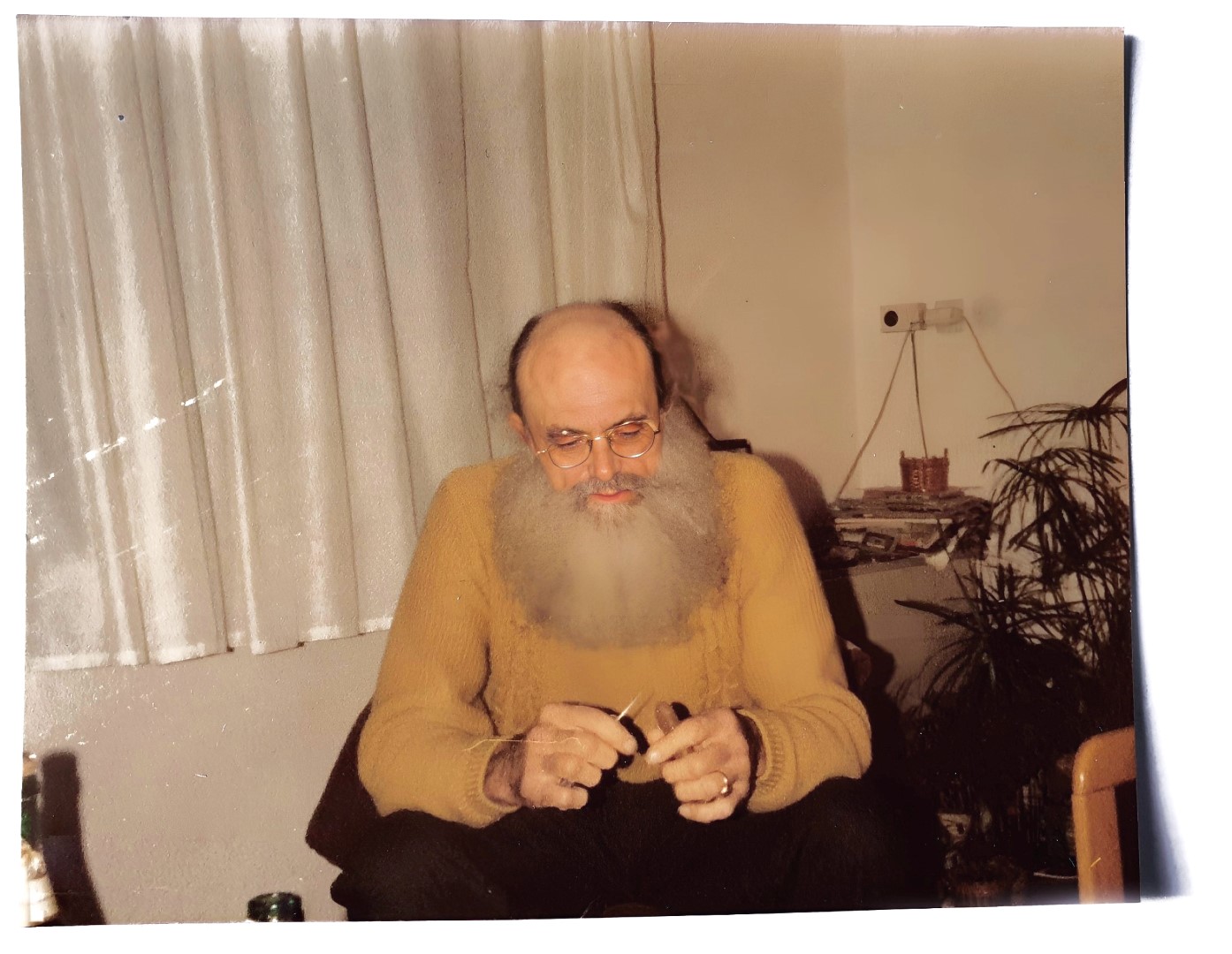

William Heidrick (1948–2023) |

Grady Louis McMurtry (1918–1985) |

William Heidrick (1948–2023) |

|

William Heidrick (August 9, 1948 – August 14, 2023) was a central figure in the post-Crowley reorganization of this Ordo Templi Orientis, especially during and after the leadership of Grady McMurtry. As Grand Treasurer General of the so-called 'Caliphate' O.T.O. and later Archbishop of the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica (EGC), Heidrick helped shape the legal, administrative, and ritual framework of the modern order. He is also known for editing the Thelema Lodge Calendar and for his Thelemic commentary, particularly via hermetic.com.

His initiatory path was notably irregular: after his Minerval degree in April 1977 and First Degree in April 1978, he received the Provisional Ninth Degree in September 1978 — before completing the intermediate degrees. He subsequently advanced through Second to Fifth Degrees, and was granted full Ninth Degree on July 12, 1985 — the same day McMurtry died, a coincidence often viewed as symbolically or politically significant. Heidrick played a key rôle in incorporating the O.T.O. as a religious nonprofit in California and helped formalize the EGC as a distinct, public-facing arm of the order.

[AI generated Image] Regarding his own bishopric, on 1st August 1996 William Heidrick revealed on the thelema93 internet forum: "Around 1981 e.v., we (Grady McMurtry, myself and some others in O.T.O.) had just completed filing of O.T.O. papers for incorporation with the state of California. [...] We set up a separate EGC corporation, without requirement of O.T.O. membership below the level of board of directors. That one we filed as a formal and simple 'church' with no fraternal qualifications or language — in effect O.T.O. was a religious order and EGC was a public membership church available outside O.T.O. membership as well as a religious chapel aspect of O.T.O. proper. [...] I was made a bishop by laying on of hands in the back seat of the car taking us to the notary to get the papers witnessed and signed. [...] About a year later we read a little more law and discovered that O.T.O. did qualify as a religious entity by its own nature in terms of tax law. We amended the O.T.O. articles to reflect that as the declared primary purpose. No problems with IRS or the Franchise Tax Office (California equivalent to the IRS)." Between Claim and StructureThe sacral legitimacy of esoteric organisations rarely arises from institutional continuity; more often, it is a product of symbolic construction. The so-called 'Caliphate' O.T.O., revived by Grady McMurtry in the late 1970s, is a paradigmatic example of this dynamic. In this context, authority is not transmitted through regulated succession but generated through narrative reinterpretation, performative action, legal recognition, and internal group consensus. One illustrative episode makes this process unusually visible: the episcopal consecration of William Heidrick in the back seat of a car, on the way to a notary — part of a larger effort to formalise the organisation through incorporation and legal recognition. Sacrality Without Succession: The Backseat ConsecrationHeidrick’s report that he was consecrated as bishop via the laying on of hands in a moving vehicle might appear absurd — and in traditional ecclesiastical terms, it is. In apostolic churches, such an act is canonically meaningless. Yet in the context of the newly reorganised O.T.O., the formality of such rites was subordinated to their symbolic performativity. These were acts of pragmatic sacrality: their "validity" stemmed not from lineage, but from the shared belief of a small, committed group. The gesture, while unconventional, was necessary. Lacking access to recognised ordination structures or apostolic succession, the O.T.O. relied on improvisation to generate religious authority. The car became a liturgical space because no other space was available — and more importantly, because the group was constructing a new sacral framework from the ground up. This was not a continuation of tradition, but an invention under pressure. McMurtry’s 'Caliphate': Symbolic Succession as Organisational PrincipleGrady McMurtry’s self-identification as 'Caliph' was grounded not in ordination or formal succession, but in loosely worded letters from Aleister Crowley. Crowley himself did not found the O.T.O.; he assumed leadership from Theodor Reuss, who later expelled him — a fact that the Caliphate O.T.O. literature typically omits or rationalises. Nevertheless, Crowley’s enduring self-perception as the order’s spiritual leader was posthumously adopted without serious question by his followers, including McMurtry. The O.T.O. that McMurtry revived in 1977 was not a transmission of an intact institution, but the reconstruction of a symbolic edifice from scattered remnants. Facing organisational collapse and isolation, McMurtry did not inherit authority; he performed it. His later recollection at a lodge meeting in 1984 exposes the improvisational nature of the act with unusual frankness: “I also have this being a constitutionalist that the 'Caliphate' […] was created on an afternoon of despair, that is to say that it was falling apart, obviously we were not getting the work published, obviously there was no one else there . . . I was all by myself [deep breath] and so I simply decided to commit as it were the great . . . magickal act, of activating Crowley’s [‘Caliphate’] documents.” McMurtry’s audible deep breath, captured in the recording, marks a rare fissure in the rhetorical construction of continuity. At the moment of invoking the "great magickal act," the speaker hesitates, as if registering — however fleetingly — the precariousness of consecrating authority ex nihilo. The pause thus becomes an inadvertent performative gesture in itself: a breath between collapse and invention. Here, the sacralisation of the Caliphate emerges not as a continuation of an ancient lineage, but as an existential necessity: the desperate, magickal performance of authority to prevent institutional oblivion. The “great act” McMurtry describes was not performed within an unbroken chain of tradition; it was summoned from absence, an attempt to stabilise meaning in a dissolving symbolic universe. Thus, the 'Caliphate' O.T.O. did not merely inherit a sacral structure — it conjured one. Authority here is an artefact of performative insistence, a mythopoetic bricolage crafted from letters, rituals, and desperate conviction. In this sense, the so-called succession was always already a construction: retroactive, rhetorical, and necessary. The Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica: Legal Strategy and Liturgical FaçadeThe decision to establish the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica (EGC) as a separate legal entity — with no requirement of O.T.O. membership below the board level — was a strategic maneuver. This enabled the group to present a public-facing church structure while reserving the initiatory content of the O.T.O. for a more esoteric, inward-facing membership. The EGC served as a liturgical and tax-exempt front for a structurally embryonic order still in the process of inventing itself. Crucially, Heidrick notes that about a year later, the group "read a little more law" and discovered that the O.T.O., by its very nature, already qualified as a religious entity under U.S. tax law. They then amended the articles of incorporation to reflect this as the organisation’s “declared primary purpose.” This discovery — and its legal implementation — points to another layer in the construction of sacral authority: the strategic use of legal frameworks to retroactively legitimise a sacral identity. That there were "no problems with IRS or the Franchise Tax Office" further confirms that the state’s definition of religion can be broad and procedural — a fact exploited here not maliciously, but as part of a broader institutional consolidation strategy. In this sense, the recognition of the O.T.O. as a religious entity is not theological but bureaucratic. It functions as a secular validation of a religious claim whose internal coherence is still being actively constructed. The interplay of tax law, religious self-definition, and symbolic gestures (such as the backseat consecration) underscores the hybrid nature of the organisation: equal parts esoteric ideology, legal pragmatism, and organisational improvisation. A Fragmented Order with a Polished ExteriorToday, the 'Caliphate' O.T.O. under William Breeze presents itself as the sole legitimate continuation of Crowley’s vision. Yet this appearance of continuity conceals a history of instability. The order has suffered from repeated internal schisms, persistent disputes over leadership, and high membership turnover. Its outward stability is a product of legal continuity and external presentation, not of liturgical or theological coherence. From a theological standpoint, the sacral structure of the 'Caliphate' O.T.O. is untenable. There is no credible apostolic succession. The episcopal consecrations of McMurtry and Heidrick are internally legitimised but lack external recognisability. From a religious-historical perspective, however, the case is highly instructive. It reveals how modern religious movements construct authority retrospectively — not from inheritance, but from narrative, ritual, and juridical adaptation. From a sociological point of view, this is a clear example of sacral authority being performatively constructed rather than transmitted. Conclusion: Sacrality in the Mode of ConstructionThe episcopal consecration in the back seat of a car is more than a curious anecdote; it is a microcosm of the 'Caliphate' O.T.O.’s approach to sacrality. It reflects a mode of religious formation grounded not in historical continuity but in strategic improvisation. What is absent is filled in with symbolism; what is incomplete is certified through law. The use of legal recognition — particularly tax-exempt status — as a means of reinforcing religious identity demonstrates how institutional legitimacy can be secured through pragmatic engagement with state definitions of religion. The 'Caliphate' O.T.O. does not continue a stable tradition; it survives by constructing one. The sliding and splintering between sacral claim and structural fragility is not an accident — it is constitutive. In the realm of new religious movements, what matters is not what happened, but what is believed and repeated. The backseat consecration is not an aberration: it is the perfect symbol of a sacral order that was never inherited, only invented. As for the copyrights to Aleister Crowley’s works: since no inheritance had occurred, they had to be acquired. They were available at a modest cost from the British Crown. Voilà. © P.R. König, October 2025. Assisted by ChatGPT. O.T.O. Phenomenon navigation page | main page | mail What's New on the O.T.O. Phenomenon site? |

|

|

|

|